Photography Book Captures Cambodian Refugees’ Struggle to Settle in 1990s Chicago

Photography Book Captures Cambodian Refugees’ Struggle to Settle in 1990s Chicago

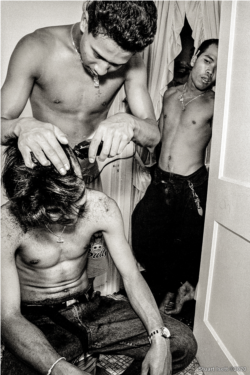

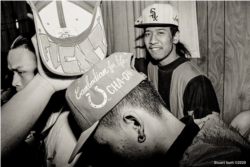

The images convey the experience of refugees and their children, as they struggled to put Cambodia’s conflicts behind them and raise their families in America’s poorest neighborhoods.

By Ten Soksreinith

CHICAGO – For Khemarey Khoeun, the images bring back memories of growing up as a child in the Cambodian community in Chicago: mothers caring for toddlers in front of an apartment block on a summer day, young men donning caps and sneakers who smoke cigarettes on a street corner, a wedding party with the couple in traditional Khmer clothes gathered in a cramped apartment.

The photos appear in a recently published book by Stuart Isett called “Krousar: On the Corners of Argyle and Glenwood.” The images convey a sense of hardship and cultural dislocation and also resilience, adaptation and joy among the community of Cambodian refugees, many of whom were trying to find their place in American society after escaping the horrors of war and genocide in their homeland just a few years earlier.

The family of Khemarey Khoeun, 40, first settled in the Austin neighborhood in Chicago’s Uptown area, one of the city’s poorest communities, after they left Sa Kaeo Refugee Camp in Thailand in 1981.

The U.S. government had accepted refugees from the inadequately administered camp, where thousands of desperate civilians had fled to escape heavy fighting between Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese Army forces in northwest Cambodia from the late 1970s to the early 1980s.

Until the age of five, Khemarey Khoeun lived in the Uptown neighborhood surrounding the intersection of W. Argyle Street and N. Glenwood Avenue, which is located a block north of the St. Boniface Catholic Cemetery. Her family then moved to the suburbs and she recalled how she saw some Cambodian youth in Uptown being drawn into gritty and often volatile gang life on the streets.

“Around that time, [Cambodian] people used to hang out at the beaches nearby, Foster and Montrose, and it got to the point where people stopped going there, because that was where the gangs were going at each other,” said Khemarey Khoeun, who is now president of the board of directors at the National Cambodian Heritage Museum and Killing Fields Memorial in Chicago. “We did not feel safe anymore.”

She explained it was understandable that many youth turned to the comradery, belonging and protection of a gang, as they grew up in an uprooted and impoverished community.

“Their parents were often not available—both of them were working—and kids were left out by their own to decide for themselves,” she said.

“And they grew up in an environment where their parents were survivors of genocide, wars, and had PTSD, traumas,” she said. “How easy it would have been for them to be recruited into the Cambodian gangs. So that had become their lifestyle.”

“We call the book Krousar, the common Khmer word for family”

Stuart Isett was a young graduate photography student at the time and from 1991 to 1994 he mingled with Cambodian youths in the area, and took the photos of them and their families.

Almost three decades later, he revisited his collection and published it as a book in collaboration with Pete Pin, a photographer based in New York City, and with Silong Chhun, a multi-media artist and founder of Red Scarf Revolution clothing brand that promotes Khmer culture and history, and a community advocate against U.S. government deportation of Cambodian-Americans.

Published by Catfish Asia books, Isett’s images were sequenced by Pin and worded by Chhun. “Krousar” sold out soon after it was released in February 2021 and it is currently unclear if another edition is planned.

Isett, the author, explained to VOA Khmer: “We call [the book] Krousar, the common [Khmer] word for family. And it's about Cambodian families. And it's also about how these young men had to form their own family in some ways, which was separate from their Cambodian families. Because they were now living in the United States, so they formed these—I don't like using the word ‘gang’—but they formed gangs.”

Isett developed an interest in Cambodia’s humanitarian crisis and conflict after visiting the refugee camps in Thailand after finishing college in the late 1980s, spawning an interest in Southeast Asia that he has maintained in his work ever since.

The images personally resonated for Chhun and Pin as Cambodian-Americans and, as the book’s blurb puts it, “they would have been the young boys in the back of the room in many of Isett’s images.”

“When I first saw [the photos], I was really, really happy, because in a sense, his photos were a reflection of how my friends and I grew up,” said Chhun, 41, explaining that, like many youths, he relied on his friends in the streets for “acceptance and value” after his family was settled in a housing project in Tacoma, WA. in 1981.

He added that the photos also capture how elements of Cambodian culture survive in the U.S.

“There are celebrations and the dancing, the older folks and the younger folks doing it,” he said. “Cambodia has a very community and village focused-culture based on, you know, just celebrating together. And despite the hardships and challenges, we have to find some light in the dark to keep us going.”

Chhun said text with the photos in the book was meant to provide context and help “humanize” the Cambodian experience and the struggle to find an identity and how to fit into American society. “We were labeled as this community that came from nothing and had to try to find a way in the country,” he explained.

150,000 Refugees Arrive

Tens of thousands of Cambodians fled to Thailand from the mid-1970s onward to escape the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime and the subsequent protracted conflict between Pol Pot’s forces and the Vietnamese Army occupying Cambodia.

Most stayed in Sa Kaeo and Khao I Dang camps; refugee camps; some 200,000 refugees passed through the latter camp until resettlement in the U.S., Australia and France, or until repatriation to Cambodia in 1993.

In 2016, a Learning Centre for the History of Khao I Dang opened at the former camp featuring an exhibition with photographs, videos and text, supported by the Thai government, UN Refugee Agency and International Committee of the Red Cross, which used to run the camp.

The 150,000 Cambodian refugees who came to the U.S. 35 or 40 years ago were dispersed by the government to cities and towns across the country, often in housing projects, eventually forming sizable communities in places such as Chicago, Seattle, Long Beach, CA., and Lowell, MA.

“Many of them came from peasant backgrounds,” said Eric Tang, Director of Center for Asian American Studies, University of Texas, Austin. “And so when they came here, employment was very difficult for them to find work and as a result, many had to remain on welfare for generations.”

“So, what happens is they are immediately tracked into urban poverty in the United States, and that makes for a unique situation of Cambodian refugees, and [other] Southeast Asian refugees,” Tang told VOA Khmer.

In addition to the struggle to lift themselves out of poverty, many of the Cambodian arrivals faced challenges associated with war trauma and mental health ailments. By 2020, the population of Cambodians in the U.S. reached 340,000 and some 13 percent continue to live under the poverty line, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

A Need to Understand the Cambodian Refugee Experience

Isett's photography book documents the recent history of this group and appears at a time where there is a growing public attention and debate about the Asian-American immigrant experience with writers such as Vietnamese-American Viet Than Ngyun and Khmer-American Anthony Veasna So gaining critical acclaim.

Sithea San, 54, said it was uncommon for her to see a book that intimately captures the Cambodian refugee experience in America and it had helped her better understand the struggle of the tens of thousands Cambodian refugees across the U.S.

“I thought my life settling into the American ways of life was hard, but seeing these photographs showed me how much harder and challenging it has been for other people,” she said, noting that she arrived in Long Beach as a 14-year-old refugee in 1981.

Khemarey Khoeun said the book would also help a younger generation of Cambodian-Americans understand what their parents went through and achieved by sheer resilience, as they grappled with trauma and raising their families amid hardships.

“There is a younger generation who are growing up, who don’t know that history and are not as connected to the recent refugee experience because they were born here as the first generation,” she said.

Chhun said, “We faced many challenges and barriers, and we still do today. But we are resilient. We are people that came from nothing and now, about 40 years later, we've accomplished so much.”