PHNOM PENH — Sann Khin’s confidence was swelling ahead of Cambodia’s commune elections on June 4, 2017.

As the opposition’s top candidate in Siem Reap province’s Kouk Thlork Leu commune, the 51-year-old rice farmer had expected about 100 people to turn out for the campaign rallies.

“But it increased up to 200 or 300. We didn’t give them money for gasoline. But they spent it on their own,” he said.

“There was a lot of support,” he added. “We knew that we were going to win.”

Less predictable was how the ruling Cambodian People’s Party would react to those local elections five years ago, and how drastically the country’s political landscape would be transformed in the ensuing years.

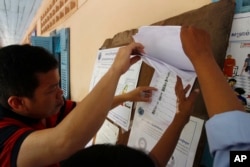

As Cambodia now prepares for the next round of commune elections on June 5, VOA Khmer spoke to commune chiefs and political observers about why the 2017 vote was such a watershed event in the country’s experiment with democracy.

Sann Khin’s victory in Kouk Thlork Leu commune was one of nearly 500 wins for the CNRP across the country that day, less than half the CPP, which won more than 1,100 communes, but a tremendous gain from the combined 40 communes controlled by the two leading opposition parties — headed by Sam Rainsy and Kem Sokha — before they united.

In Siem Reap province, the CNRP crushed the CPP, winning 50% of the votes to the ruling party’s 41%, and 56 commune chief posts to the ruling party’s 44, according to National Election Committee’s data.

Sann Khin and his victorious colleagues would not remain in their positions long.

On November 16, the Supreme Court announced that the CNRP was being dissolved amid accusations that its leaders were plotting to topple Prime Minister Hun Sen’s government. Opposition officials and political observers said the move was engineered to remove the CPP’s only legitimate rival because it feared losing the national election in 2018.

“They are afraid. That is why they dissolved us,” said Khin. “If [the CNRP] still existed, the ruling party would lose the election. People were ready to win. We would have completely won in the 2018 election.”

He heard the news of the CNRP’s dissolution over the radio, then came the calls from party officials. There were no mass protests, as the party’s president, Sam Rainsy, and other opposition leaders had already fled the country, fearing the same fate as Kem Sokha, the deputy president arrested for allegedly conspiring with the United States to wage a color revolution.

First, the ruling party tried to convince Khin to defect to the CPP. When he refused, police and military police removed party placards from in front of his home and then began intimidating his family, forcing them to go to Thailand for three months.

“It was very cruel,” said the father of five.

According to Phil Robertson, deputy director of the Asia division of Human Rights Watch, Hun Sen and his ruling party “decided to destroy Cambodian democracy by fabricating a bogus, politically motivated case to ban the CNRP…and returning to their tried and true methods of intimidation and violence to hold on to power.”

It was a stark shift after an election that many agree may have been the most free and fair in Cambodia’s modern history. Robertson noted there was far less violence and intimidation from the ruling party than usual, an assessment shared by commune chiefs who spoke with VOA Khmer.

And when problems did arise, they were resolved by a bipartisan National Election Committee that formed during power-sharing negotiations that followed the 2013 national election, said Koul Panha, former executive director of the Committee of Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia and now the advisor to that organization.

That meant the election was also more open and transparent than past elections, leading both parties to ultimately accept the results. And it left little doubt that the CNRP was an existential threat to the CPP’s stranglehold on power since peace accords returned relative stability to Cambodia in the early 1990s.

“The voters had confidence in the opposition party since they were merged,” said Koul Panha. “Due to the increasing support for the opposition party, the ruling party amended the election law to target the opposition party.”

Those changes, in the works prior to the 2017 elections, allowed the CPP-controlled courts to eliminate political parties or leaders convicted of criminal offenses, along with other changes empowering the courts and ruling party to sideline or silence the opposition.

Sok Eysan, a CPP senator and spokesman, rejected claims that the ruling party intentionally sought to dissolve the opposition party to secure the party’s power, adding that “the opposition party has acted illegally.”

Mann Champa, a 40-year-old woman who joined the opposition party in her teens, was another CNRP commune chief who came to power in Siem Reap province in 2017. She said her campaign and brief time in office went fairly smooth, even in relations with ruling party colleagues on the commune council.

She heard of the party’s dissolution via Facebook, and said she stayed on for a few days to pass on her work. “We know the law,” she told VOA Khmer. “We can’t protest since it is the state’s law. We just finished up work and then stopped.”

“I also felt regret since we were elected by villagers to serve them for a term,” she added.

Mann Champa is among the many opposition officials and members who have joined the new Candlelight Party, an overt allusion to the Sam Rainsy Party symbol made popular through grassroots work and elections during the 1990s and 2000s. The party united with Kem Sokha’s Human Rights Party ahead of the 2013 national election, when the CNRP first emerged as a major challenger to the CPP.

Mann Champa, a mother of two, predicted the party might be dissolved again, but hoped the CNRP would be prepared with lawyers and public protests this time to challenge the move.

“We should not be silent,” she said.

Robertson of Human Rights Watch said, “it’s likely that the 2022 election will be a charade of democracy without the real possibility of the ruling power having their power challenged in any way.”

However, Astrid Norén Nilsson, a scholar of Cambodian politics at Lund University in Sweden, said that all things considered, the Candlelight Party “is in quite a good place” compared to other opposition parties, several of which are led by former CNRP officials.

“There are several credible opposition parties taking part, but they constantly have to navigate the fear of dissolution and operate in a political space that has radically shrunk,” she said.

“So, I would say these elections are much more ambiguous in terms of how competitive they will be.”