Keo Somony had not even been sworn into his new role on the commune council before his life started falling apart.

In the June 5 commune elections, the longtime Ministry of Health official became the opposition Candlelight Party’s only councilor in Chhbar Ampov 1 commune in the capital city.

But on June 21, five days before the results became official, he got a call from the deputy head of the ministry’s Mental Health and Drug Abuse Department, where he was a mental health specialist, who told him to “say goodbye to the boss.”

He went to meet Chhit Sophal, the head of the department, who placed a brown envelope on the table in front of him. The letter inside said Keo Somony was terminated for “disciplinary measures” from June 14 onward, signed by Health Minister Mam Bunheng.

Out of a job, Keo Somony’s wife and children soon moved out of their house, leaving him alone. He told VOA Khmer that his family had urged him to stay out of politics.

“But I didn’t listen,” Keo Somony said. “So I accept all of these issues.”

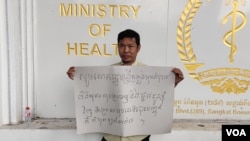

Now, Keo Somony is focused on getting an explanation from the ministry that employed him for more than 20 years.

“This is against the law. I think this is political discrimination rather than law enforcement,” Keo Somony told VOA Khmer.

“It also shows that if others [do] like me, they have the same fate as me,” he said.

At least three civil servants who are members of the opposition party have been removed from their posts in 2022, according to the Candlelight Party.

Cambodia’s Common Statute of Civil Servants requires ministries to afford government employees the right to receive a justification for the termination verbally or in writing, and then a chance to review their personnel file, call witnesses, choose a defender, and give written or verbal explanations.

Keo Somony wasn’t even given a chance to grab his old documents before being ushered out of the building after being fired, and the ministry has refused to give him, or the media, an explanation.

Chhit Sophal refused to talk about anything that related to Keo Somony when reached by telephone. “I have no comment. I am not in the discipline committee. I’m sorry, I’m busy,” he said before turning off his phone. Minister Mam Bunheng picked up his phone, but hung up after a VOA Khmer reporter introduced themself and started to ask a question.

An official at the ministry, who asked not to be named due to the risk to his job, said he “deeply regrets” the ministry’s decision and added the ministry should explain the reason Keo Somony lost his job.

“But it’s helpless,” the official added. “We are not the leaders, and we don’t know about the internal [situation], something behind the scenes.”

'No one dares to do it'

For nearly three decades, Keo Somony built his career in Cambodia’s public health sector. Born in 1970 in Kandal province, he wanted to be a teacher. But he missed the deadline for applying for the pedagogy program and instead entered the nursing program at the Technical School for Medical Care in 1991.

Soon after graduating in 1995, he was selected to work in the Ministry of Health. He trained other health workers in provinces while continuing his own studies in mental health. Shortly after coming back from an internship at the Philippine General Hospital’s psychiatric ward in 2000, Keo Somony entered the master’s degree program in clinical psychology focusing on trauma at the Royal University of Phnom Penh.

The new qualification eventually allowed him to switch to the Department of Mental Health and Drug Abuse at the ministry, earning about $400 a month for the eight years leading up to his ouster.

As he was ascending up the public health ranks, his wife, Kuy Khim, was becoming increasingly active in opposition politics. In 2012, she became a commune councilor for the Sam Rainsy Party. And then in 2017, she won a seat with the newly formed Cambodia National Rescue Party, serving until it was dissolved by the Supreme Court in 2017.

As the space for dissent in Cambodia closed, she decided to stay away from politics, and their son and daughter agreed that the family should lay low.

Dozens of opposition activists would be prosecuted in the ensuing months, and government critics were regularly jailed for offenses ranging from organizing protests to posting satirical messages on Facebook.

Keo Somony too had been involved with the opposition for years. An admirer of Sam Rainsy since his days as the minister of finance in the early 1990s, he joined Rainsy’s Khmer Nation Party when it launched in 1995, and was appointed the party’s grassroots leader in Chhbar Ampov 1 commune a few years later.

But he kept a relatively “low profile” and carried out his political work “indirectly,” he said. Still, his loyalty was not a secret to higher-ups at the ministry.

Shortly after the CNRP was dissolved, Somony said he received a text message from Chhit Sophal seeking to lure him to join the ruling Cambodian People’s Party. Somony declined.

Instead, he decided to replace his wife on the newly formed opposition party’s commune ticket. The Candlelight Party, which uses a similar visual symbol as the former Sam Rainsy Party, was launched last year by longtime opposition officials.

“I want this commune to have a multi-party contest so that it helps improve service for people. Having one party won’t serve people smoothly. We need the opposition voice, and that benefits our people, thus I decided to run the election.” he told VOA Khmer.

“If I don’t come forward to stand as a commune candidate, no one dares to do it,” he added.

Ly Neh, deputy chief of the next-door Nirouth commune, also from Candlelight Party, told VOA Khmer that Keo Somony followed the guidelines for civil servants seeking public office, and even received approval from the ministry — making his firing all the more unjust.

“I think Mony decided to run this election for a good cause,” Ly Neh said, adding that Somony tried to convince others to run in the election.

“In Chhbar Ampov 1, if he didn’t take over his wife’s candidacy to stand in the election, no one would do it. There would be no competition, and there would be one party.”

Fighting back and carrying on

Political commentator Meas Nee said Somony’s sacking after the election appeared to be an obvious case of political discrimination.

“If you are flagged as outspoken, you don’t have to be involved with the opposition to be sidelined,” he said. “You are not going to be promoted or hold an important position — unlike those who flatter the [ruling] party.”

And there isn’t much the Candelight party can do about it, he added.

“It’s easy to say that the opposition party should do something to support their members in such case. But this is not a long-term solution,” Meas Nee said. “We all know that besides the ruling party, no other party can support their members financially like in such cases. So the only solution is to guarantee justice.”

Keo Somony said he is taking his fight to court, having hired a lawyer with support from the Candlelight Party, who is processing a lawsuit over his termination. However, a Candlelight Party official said they are yet to take action in the case, but would try to help Keo Somony obtain legal support if he needs it.

Lawyer Sek Sophorn told VOA Khmer that he could not discuss Keo Somony’s case specifically, but said it was important to know if there were official warnings, regarding specific mistakes or crimes committed by Keo Somony.

“So, if there weren’t any mistakes that could be found with him, the removal of him could be a mistake,” Sek Sophorn added.

Back in Chhbar Ampov 1 commune, Keo Somony is carrying on his wife’s legacy as the second deputy commune chief, whether she likes it or not. In the last local election, five years ago, voters in the commune elected CNRP members to four of nine councilor seats. Now it’s merely Keo Somony for the Candlelight Party and eight members of the CPP.

Commune Chief Huot Pov said the composition of the commune council doesn’t make a difference. “With or without any other political party, we can still serve people following our roles and responsibilities. Nothing changes,” said Huot Pov, a member of the ruling CPP.

He said he didn’t have any comment on the Ministry of Health’s sacking of his fellow commune councilor, but added: “All I know is that one should not hold two positions and get two salaries from the government like that. So, he has to choose one.”

Keo Somony is trying to stay busy, and waiting for his first $200 salary payment from the commune to come through at the end of August.

He was recently assigned to resolve a conflict between two neighbors. One commune resident was pressing ahead with repairs to their house, and wanted to place their electricity meter on the house next door, angering its owner.

Keo Somony said he successfully resolved the conflict, using strategies he learned in psychology, something the previous commune council couldn’t do despite six months of trying.

“This work is quite new to me,” he said. “But I think my previous background helps.”