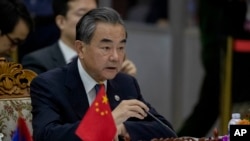

Late last year, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi gathered together his country’s envoys for a pep talk, telling them they needed to be more assertive in representing Beijing’s interests overseas and vocal in defending the Chinese Communist government from criticism.

He complained that China was being bullied by Western powers over its human rights record, and he instructed them, according to Chinese press reports, to display a much stronger “fighting spirit.”

And since December, China’s diplomatic corps has done exactly that, in what Western officials and analysts say is a coordinated campaign lauding President Xi Jinping and threatening “counter-measures” against critical foreign governments.

As international criticism has mounted about China’s initial handling of the coronavirus outbreak — and amid growing accusations Beijing may have obscured the origins of the deadly virus, covering up the severity of the outbreak in the city of Wuhan — Beijing’s diplomats have clashed with host countries in a way seldom seen in peacetime.

According to John Seaman of the French Institute, “China’s public diplomacy has gone into overdrive. It appears well coordinated, with varying degrees of dogmatism, divisiveness and moderation.”

But even before the coronavirus outbreak, the tone and temper of Chinese diplomacy started to sharpen, with Chinese envoys in Western capitals exhibiting a truculence that Western officials say is a far cry from what was seen during the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, who ruled as the China’s paramount leader from 1978 until retirement in 1992.

Traditionally considered the more circumspect of the world’s ambassadors, China’s envoys have had a makeover.

Among the first of China’s envoys to heed his boss’s instruction was Gui Congyou, the ambassador to Sweden. He pushed back sharply on Swedish criticism of alleged Chinese human rights abuses, warning in an interview with the country’s Göteborgs-Posten newspaper of severe consequences if the fault-finding didn’t stop.

“The Chinese government absolutely cannot allow any country, organization or person to harm China’s national interests. Of course, we must take countermeasures,” he said, mentioning likely disruption to Swedish cultural exchanges with China. “Economic and trade relations will also be affected,” said Congyou, who started his career as a policy researcher for the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China.

Sweden’s ties with China have been increasingly strained in recent years. The detention of Swedish citizen and Hong Kong bookseller Gui Minhai, who disappeared while vacationing in Thailand and has been held in China since 2015, started the slide.

Since Gui Congyou’s newspaper interview, several other Chinese envoys have been castigated by their host countries for promoting ‘fake news’ on social-media sites — or for what have been viewed as offensive comments.

Nicknamed by the media “wolf warriors” — after a blockbuster movie in which Chinese special forces vanquish American mercenaries in Africa and Asia — China’s envoys seem determined to break with older traditions of China’s more discreet diplomacy.

Soon after Gui Congyou warned his Swedish hosts of “bad consequences,” his counterpart in Canada, Cong Peiwu, threatened Ottawa with “very firm countermeasures,” if Canadian lawmakers pressed ahead with sanctions on China over alleged Chinese human rights abuses against Muslim Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking Muslim minority in northwest China.

Since 2015, more than 1 million Uighurs have been detained in what Chinese officials describe as “vocational education centers” for job training, but critics describe as internment or concentration camps.

Cong Peiwu warned that if Canada sanctioned China “it suddenly would be a very serious violation of Chinese domestic affairs.” China’s ambassador in the U.S., Cui Tiankai, also issued warnings about sanctions being proposed, too, in Washington, saying, “Some people in this country are pointing fingers at the governing party and the national system of China, trying to rebuild the Berlin Wall between China and the U.S. in the economic, technological and ideological fields,” Cui said.

But since the coronavirus outbreak, the tone from the “wolf warriors” has become even more fractious, according to Western diplomats and analysts. They expect the combativeness is likely to intensify as international demands mount for an independent inquiry into the origins of the deadly virus and into the suppression of reports by Chinese authorities about COVID-19’s capacity for human-to-human transmission.

Some Western leaders and officials, although not all, have suggested the pathogen may have escaped from a research lab in Wuhan, the city where the novel virus was first detected late last year.

In Paris, French authorities reprimanded last month Chinese ambassador Lu Shaye, in response to an online post from his embassy claiming France had abandoned its older citizens, leaving them to “die from starvation and disease.” The French foreign ministry said in a statement: “Some recent public statements by representatives of the Chinese embassy in France do not conform to the quality of the bilateral relationship between our two countries.”

Under the leadership of the 55-year-old Lu Shaye, a former envoy to Canada, and a one-time deputy mayor of Wuhan, the Chinese embassy in Paris has been lauding what it describes as Beijing’s success in quelling the coronavirus outbreak while scorning the handling of the pandemic by Western countries.

The attacks took French diplomats by surprise. France has worked hard to improve relations with China, and last November, French President Emmanuel Macron went to Beijing on a state visit that was widely seen as undercutting a more robust European Union strategy toward China agreed upon just months before.

In Cyprus, too, the Chinese envoy, Huang Xingyuan, has prompted the disapproval of his hosts for saying the world was embarrassed by how quickly China had solved the virus outbreak, and had resorted to “blame shifting and lies.”

Additionally, tweets and statements by Chinese diplomats have prompted pushback not only in Europe — Kazakhstan, Iran, Pakistan, Brazil and Singapore, to name a few, have seen arguments flare.

In Sri Lanka, the Chinese embassy complained on Twitter: “When westerners publish their opinions, it’s called freedom of speech, no matter how false. When Chinese say something different from them, it’s called a disinformation campaign. Hilarious double standards.”

China’s diplomats also have lashed out in India in response to calls for Beijing to offer reparations for the coronavirus pandemic, saying the compensation demands are “ridiculous & eyeball-catching nonsense.”

In Venezuela, a country Beijing has seen as a “socialist ally,” Chinese diplomats tweeted that officials in Caracas should “put on a face-mask and shut up.” That retort was in response to Venezuelans referring to COVID-19 as the “Chinese” or “Wuhan” virus.

China’s official publications are unapologetic about the combative diplomacy. “Throw away your illusions and prepare for a fight,” announced recently the People’s Frontline newspaper, which is run by China’s People’s Liberation Army.

“The world and Chinese diplomats have changed,” announced the Global Times, a Chinese Communist Party publication. In an opinion piece run last month, it said, “the days when China can be put in a submissive position are long gone. China's rising status in the world requires it to safeguard its national interests in an unequivocal way.”

The Chinese people, the Global Times said, “are no longer satisfied with a flaccid diplomatic tone,” adding that China has not abandoned Deng Xiaoping’s guiding principle for diplomacy — “hide your strength, bide your time.” The newspaper said: “The ‘Wolf Warrior’ style of diplomacy doesn't contradict this principle, it's just less subtle.”

“‘Wolf warrior’ Chinese diplomats have sought to outdo each other by challenging narratives about COVID-19, while propagating disinformation about the origins of the virus,” says Robin Niblett, director of Britain’s Chatham House.

Some Western analysts believe the pugnaciousness of Chinese diplomacy is at its root defensive — a reflection of the Chinese leadership feeling cornered, a case of throwing “mud when provoked,” says a report published last week by the Netherlands Institute of International Relations, a think tank based in The Hague.

Whatever the root causes, the diplomatic offensive risks backfiring, says former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd.

In a commentary Wednesday for Foreign Affairs magazine, Rudd said: “Whatever China’s new generation of ‘wolf-warrior’ diplomats may report back to Beijing, the reality is that China’s standing has taken a huge hit [the irony is that these wolf-warriors are adding to this damage, not ameliorating it]. Anti-Chinese reaction over the spread of the virus, often racially charged, has been seen in countries as disparate as India, Indonesia, and Iran. Chinese soft power runs the risk of being shredded.”