The UN-backed Khmer Rouge tribunal is steadily working toward it biggest, more complicated trial to date, but that trial has been overshadowed in recent months by the court’s handling of two additional cases, which has seen the resignation of one UN judge and an emergency meeting with the UN’s top legal counsel and Cambodian officials.

A growing number of court observers now say the court’s approach to cases 003 and 004 is derailing its credibility, even as it prepares to try four Khmer Rouge leaders for one of the worst atrocities of the 20th Century.

The Khmer Rouge tribunal will face its most difficult trial some time next year. As judges and prosecutors and their staff work toward the trial of Nuon Chea, Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary and Ieng Thirith, they are also facing a growing chorus of criticism.

At stake, many court observers say, is the court’s overall credibility.

“The Khmer Rouge court must leave a legacy if it wants to see success,” said Ou Virak, the president of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights. “Firstly, to try those who are the most responsible persons for the mass murders of the Khmer Rouge regime. Secondly, they must leave a judicial system a model in Cambodia.”

The court is struggling now on both counts. The handling of cases 003 and 004, which would come after next years trial, has caused the most concern. But so too has the example the court has shown overall, according to numerous interviews with independent observers both in Cambodia and internationally.

Court monitors, victims’ groups and victims themselves say they want those two cases to go forward, against the many public objections of Prime Minister Hun Sen.

However, the investigating judges in charge of those cases have signaled they want those cases wrapped up or dismissed quickly. The judges, Siegfried Blunk and You Bunleng, said earlier this year they had serious doubts about whether the five suspects in those two cases qualify as “most responsible” for Khmer Rouge atrocities.

Blunk resigned earlier this month, citing public objections to two cases by top government officials that made a making a decision perceived as fair impossible. The UN’s undersecretary-general for legal affairs, Patricia O’Brien, told Cambodian officials they must cease making public comments that oppose the cases.

However, many observers now say the court’s reputation is already in serious jeopardy.

“The argument over cases 003 and 004 has already badly damaged the court’s reputation, revealing internal rifts and political interference,” said John Ciorciari, a professor of public policy at the University of Michigan. “It will be difficult to undo that damage. If cases 003 and 004 move forward, they will likely generate continued disagreement and interference and further delay the start of the most important trial, Case 002, which is increasingly in peril due to the age and ill health of the defendants.”

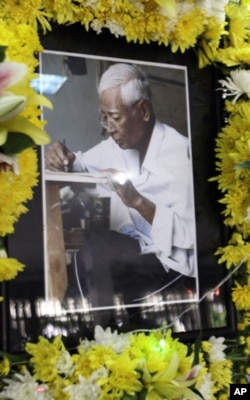

The urgency of Case 002 was underscored earlier in September, when a key witness and one of the few survivors of the notorious Khmer Rouge prison Tuol Sleng, Vann Nath, died after a heart attack.

Meanwhile, leaders to be tried in that case have had to be subjected to health screenings on whether they were fit to stand trial at all. Were the trial to fail to try those four, it would have spent millions of dollars to convict Kaing Kek Iev, the head of Tuol Sleng prison better known as Duch, whose case was relatively simple but whose 2009 trial is still awaiting a final decision at the court.

But to many critics of the court, known officially as the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, or ECCC, the main problem for the tribunal’s credibility lies in the office of investigating judges.

Blunk’s resignation may be an opportunity for the court to regain some credibility, said John Hall, a law professor at Chapman University.

“If those investigations are carried out by the co-investigating judges in a transparent, honest, and thorough fashion, that will do much to restore credibility of the ECCC,” he said. “If the co-investigating judges simply sit on their hands and fail to carry out adequate investigations, then I think there it is a strong reason for the entire legitimacy of the tribunal to be called into question.”

The court’s failing to properly investigate the cases “would be appropriate for the UN to withdraw its supports from the tribunal,” he added.

However, the court defends its work.

“This court is moving successfully on Case 001, which we have almost finished, and in coming days will declare the verdict for, and we also plan to start Case 002,” tribunal spokesman Huy Vannak said.

The court has decided to split Case 002 into segments to “expedite the case for the advantages of justice,” he said. “And the court has been welcomed by many observers and donors.”

However, the court has been under increasing pressure since April, when the investigating judges hastily concluded their investigation into Case 003, failing to interview the two key suspects, military commanders Meas Muth and Sou Met, both of whom the former UN prosecutor said in 2008 were among the upper echelons of leadership.

The current international prosecutor, Andrew Cayley, immediately appealed for the judges to renew their investigation, calling on them to interview the suspects and visit key crime sites.

“Available information suggests that the ECCC Co-Investigating Judges made up their minds early on cases 003 and 004 and conducted a half-hearted investigation,” Ciorciari said.

In June, the US-based Open Society Justice Initiative called on the court to “conduct an independent investigation into serious allegations that the co-investigating judges…are deliberately stymying investigations.”

The judicial-monitoring group renewed those calls last week, after the investigating judges made a decision that could include many victims from participation in Case 002—a major mandate for a court that was built in part to create a sense of national reconciliation over the mass torture, murder, abuse, starvation, forced labor and other crimes of the Khmer Rouge.

In an interview, James Goldston, executive director of OSJI, said the court is not meeting international standards, especially in its investigations.

“ECCC judicial officers should act like other courts to address international crimes,” he said. “Those are required to carry out investigations in the manner that is effective, capable of leading to the identification and punishment of those responsible, independent from external pressure, prompt and open to an element of public scrutiny.”

Martin Nesirky, spokesperson for the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, said the UN would support an independent court free from pressure.

“The judges at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia must be allowed to function free from external interference by the Royal Government of Cambodia, the United Nations, donor States, and civil society,” he said.

The question of public scrutiny and transparency has dogged the tribunal since before its inception. Since it was established, after much wrangling between the UN and Cambodia, in 2006, the court has been plagued allegations of corruption that were never fully addressed in the public.

That same secrecy now obscures the investigation of cases 003 and 004, Goldston said.

“Such that victims of the Khmer Rouge crimes who are potentially civil parties have not been given a proper opportunity to join the proceedings,” he said. “The manner in which the investigations in cases 003 and 004 have been carried out contrasts markedly with the ample information the court provided to the public with respect to its investigations in cases 001 and 002.”

The improper handlings of those cases have repercussions beyond the investigating judges, he said.

“The positive impact of a successful trial of the top leadership in Case 002 will be diminished if these concerns are not convincingly addressed,” he said.

Brad Adams, the Asia director for Human Rights Watch, said after $200 million, the tribunal should be able to expand its scope beyond the five leaders currently detained at the court.

“Those five people have been implicated in very serious crimes,” he said. “But they did not do all of the shooting.”

Khmer Rouge complicity reached far into the ranks of the regime, beyond the key decision makers, he said. Trying cases 003 and 004 would bring forward “some of the most serious people…who were responsible for thousands and thousands, tens of thousands, of deaths.”

“In other courts, what they do is that when they get evidence presented to them, they investigate it,” he said. “They investigate it by talking to the accused if they can, by talking to witnesses, by looking at documents, by talking to experts. And it seems that none of these have been done in cases 003 and 004.”

The investigating judges have not done enough, he said.

“Why haven’t they been out in the field, every day, every week, every month, interviewing people, trying to find out what happened in the crime sites?” he said. “That’s what professional investigating judges would do. So this is very unusual. It’s the poorest performance of any of the courts that the UN has been involved with, and that’s why it is widely believed, widely accepted globally, that this court in Cambodia is the worse of its kind.”

Peter Maguire, a US law professor and author of a book on the Khmer Rouge, said the investigating judges have “caved to political pressure.” Case 002 will be their last trial, he said. “Time for them to go home.”

The handling of cases 003 and 004 by the investigating judges has also raised questions among Cambodian observers like Hang Chhaya, executive director of the Khmer Institute for Democracy.

“If they are not active on this issue, or do not investigate thoroughly, I believe this will become part of history, and the judges involved will be implicated in that history,” he said. “And I believe they will regret it in the future.”

Pung Chhiv Kek, founder of the rights group Licadho, said the court still has a chance to improve its legacy, by having the prosecutors and investigating judges cooperate to continue with the cases.

“I think if there is no compromise, the Cambodian people will be very much disappointed,” she said. “As for the [court’s] reputation, I can’t guarantee it, because at the beginning, we saw that the court was working very well, so we all hope to see justice, the truth, and we imagine the court will be a model.”

The actions of the investigating judges in cases 003 and 004 have raised lingering questions of political interference from Hun Sen and senior government officials, some of whom are former Khmer Rouge cadre themselves.

Blunk cited public statements from the premier, the foreign minister and the information minister in his resignation statement.

Cioriari, of the University of Michigan, said if the cases do not proceed, “most observers will justifiably conclude that the cases were dismissed for political reasons—including donor fatigue and frustration, as well as government opposition.”

“The tribunal’s best option is to proceed with the cases in earnest, delivering a credible verdict or issuing very well-reasoned, well-documented legal grounds for dismissal,” he said. “But those outcomes are unlikely.”

The accusations of political interference also hurt the court’s role as a model for the Cambodian judiciary, which is notoriously corrupt and ineffective.

Ou Virak, of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights, said the tribunal has not been able to fully dispel the accusations of corruption, including kickbacks from staff members, and political interference.

“So this indicates that the court cannot be a fully good model at all,” he said. “For the corruption issue, no one has taken responsibility for it, and in my view that’s a danger for the court. As to the other issue, of political interference, the court seems to just follow the government’s position and also seems to be under the government’s influence.”

“All judges and judicial officials have sacrificed to work in the court because they expect to have an important legacy in reforming the legal system in Cambodia,” the tribunal’s Huy Vannak said. The court’s legacy can be assessed only at the end of its work, he said, but it has already changed people’s attitudes.

“We’ve seen about 100,000 people have traveled to the court,” he said. “They think the court is a place classified as open, to give them a chance to understand legal procedures.”

Not everyone sees it that way.

Adams said that beyond acting as a role model for the Cambodian judiciary, the tribunal could have been, in part, a model for the society at large, where criminals often go unpunished.

“When we talk about Cambodia today, there is impunity for the leaders,” he said. “There is impunity for senior military figures in the government, people in the Ministry of Interior.”

He cited still-unresolved killings under Untac, the 1997 grenade attack on opposition protestors and the coup that followed later that year, violence in 1998 demonstrations and the continued violence of land grabs as instances that have so far gone unpunished.

“The Khmer Rouge trial can be part of the answer,” he said, “but even if the Khmer Rouge trial went perfectly it wouldn’t address what’s been going on in Cambodia for the last 20 years.”

Suy Mong Leang, secretary-general for the Council of Minister’s council for legal and judicial reform, told VOA Khmer that no matter what, the tribunal will have helped the national courts.

One lesson, he said, is that more money is needed in the national courts. “There needs to be a budget for them to function,” he said.

Another, he said, is the adaptation of information technology. “If we can bring that and adapt it in the local courts, then that is good,” he said.

Still, he said, Cambodian courts deal with myriad crimes and offenses, where the tribunal is only focused on atrocity crimes. The national courts will have to develop more as it works with other types of crimes.

While there is no consensus on how important the full trials of cases 003 and 004 would be to the court’s legacy, it is clear that Case 002 will need its fullest attention.

The three men and one woman to be tried in that case are the top-most surviving leaders of a regime that oversaw the deaths of at least 1.7 million people. They are getting old, and the court is now in its fifth year.

“The most important case for the ECCC is Case 002,” Ciorciari said. “Continued delays raise the likelihood that some or all defendants will pass away or become too ill to stand trial before a judgment is rendered. If the ECCC is unable to complete case 002 successfully, it will largely be regarded as a failure.”