Cambodia has become increasingly reliant on China for aid. But critics warn that financial support from China is not well tracked and likely means the country has undue influence over the government, and that could mean more trouble down the road as Cambodia looks toward greater development of its own.

China’s financial help, which improves Cambodian infrastructure, military and other sectors, has long been a concern of rights groups and the opposition, who warn that such aid means China can influence Cambodian policy.

China meanwhile is looking for natural resources, cheap labor, opportunities for markets and investments. China has played a major role in the garment sector, where it has access to cheap labor and land concessions, as well as development projects across the country.

Cambodian National Rescue Party lawmaker Son Chhay says China is typically the one who benefits from its relationship with Cambodia. “We’ve never seen that being aligned with China has helped Cambodia’s economy,” he said. “Only exploitation, land grabbing, logging, dams that affect the environment, and construction that has no quality.”

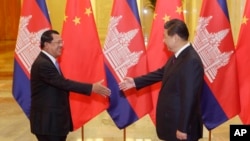

Cambodia continues to strengthen its ties with China. In November, Prime Minister Hun Sen attended a summit there, where China pledged more aid to help develop the economy—about $500 million per year.

Government spokesman Phay Siphan said China helps Cambodia develop, and that’s what Cambodia is looking for.

China has helped Cambodia with security, too. In 2013, Beijing provided 1,000 weapons and 50,000 rounds of ammunition, a donation that followed the delivery of 26 Chinese trucks and 30,000 uniforms, as well as the sale of a dozen military helicopters worth some $200 million. Cambodia will have to pay that off over time.

In May this year, China offered $33 million in concession loans and a donation of $112 million. Hun Sen later said the money was for the construction of a stadium, to host the 2023 Southeast Asian Games.

At the Apec Summit in November, China offered $40 billion to establish its Silk Road fund, which will help Asean countries with development and trade cooperation.

John Ciorciari, a public policy professor at the University of Michigan, says the Cambodian-Chinese partnership continues to grow closer, economically and politically, for relatively low costs.

“China provides investment and occasional political backing, helping Cambodia’s leaders grow the economy in a way that bolsters the position of the incumbent CPP,” he said in an email. “In exchange, China seeks easy access to resources and labor and periodic diplomatic support.”

In 2012 then-President Hu Jintao met with Hun Sen ahead of an Asean Summit that Cambodia was hosting. After pledges of increased bilateral trade from China and a $70 million loan package, Cambodia derailed an Asean initiative to push harder in talks over the South China Sea.

Ciorciari says that kind of relationship has brought economic growth to Cambodia, but at a risk to the country’s independence and a risk to Asean unity.

“If China tries to use its leverage in Cambodia to that effect, diplomatic tension in the region will rise, and it is not clear that either China or Asean would gain from a polarization of Southeast Asia,” he said.

And much of the benefit isn’t to the country as a whole, he said, but rather to the Cambodian elite.

“The relationship has spurred economic activity in Cambodia, but it also helps Cambodia’s leaders resist international pressure to reform and to put greater priority on issues such as environmental protection and human rights,” he said. “On balance, it has done more for Cambodian elites than for ordinary people.”

Meanwhile, Cambodia’s relationship with China has been less rocky than with the US, which in 2009 canceled the shipment of 200 military trucks after Cambodia deported Uighur asylum-seekers to China. (Fourteen deals between China and Cambodia followed—worth some $1 billion—followed by delivery of Chinese-made military vehicles and uniforms.)

The following year, then-US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned against too much dependence on China.

“You don’t want to get too dependent on anyone country,” Clinton told a group of Cambodian students on a visit to Phnom Penh in November that year. “There are important issues that Cambodia must raise with China," she said, pointing to a string of Chinese dams along the Mekong River that were a potential threat to the region’s ecology.

Those dams have continued to be a concern, including in Cambodia 19 hydropower dams and coal plants linked to Chinese investment. That could provide power to 70 percent of Cambodian households by 2025, but it could also wreak havoc on fishing populations and the lives of people living near the dams.

Phay Siphan said Cambodia is gaining from its relationship with China, while retaining its independence. “Those who raise this do not understand, and those are aims to attack the livelihood of Cambodia,” he said. He denied that Cambodia works for China’s interests.

Still, many political observers warn caution.

Ou Virak, chairman of the board for the Cambodian Center for Human Rights, says Cambodia must avoid becoming manipulated by China, which is growing in power across the region.

“The CPP is moving toward China,” he said, “while the opposition party doesn’t know what policy it has.”

Asean, which is working toward even greater economic integration late next year, can be threatened by China’s bilateral relationships with Southeast Asian nations, he said. “If China grabs one of the Asean countries in the region, Asean will be locked,” he said. “In the past, China relied on Burma, but after Burma changed direction, toward the West, only Cambodia is left to be China’s puppet.”

Son Chhay said he worries that Phnom Penh’s debts to Beijing pave the way for big benefits to China in the future—without much concern for sustainable development in Cambodia.

“What is bad is that Cambodia is borrowing money from China to develop the country, without transparency,” he said. What’s more, the borrowed money usually goes to pay for projects undertaken by Chinese companies, which then “affect the environment.”

Dam construction leads to deforestation, he said, and the sale of expensive electricity back to Cambodia, “which contradicts the contribution to the country’s development.”

Other observers say the relationship is unlikely to change. Henri Lecard, a historian and scholar, said Cambodia and China get along, “since the two are functioning one-party states.”

There are good outcomes, too. The Ministry of Tourism says Chinese are now the No. 2 visitors to the country, behind the Vietnamese. Of 4.2 million visitors to Cambodia last year, more than 460,000 were Chinese.